Intro

This is Time's Corner, an occasional newsletter by Christian Leithart. I’m co-founder of Little Word and editor of Good Work magazine. By day, I teach make the most of summer break, and by night, I edit this newsletter.

I wrote about AI last summer, and some of what I say below is copied from that newsletter. The rest is based on articles I’ve read in the past year. You’ll also see a bevy of links if you care to read more on the subject.

My go-to naysayer when it comes to AI is Gary Marcus, an AI researcher who’s been active in the field for decades. He’s not against artificial intelligence. He’s against people lying about what it is actually capable of. I encourage you to follow his Substack for a healthy dose of reality (which AI models are incapable of accessing).

Also, I admit AI is a vast field and I’m conflating many products (language models, image generators, self-driving cars) that should probably be tackled separately. Feel free to correct me. Since I’m not a computer, I won’t pretend to be right all the time.

Artificial Artificial Intelligence

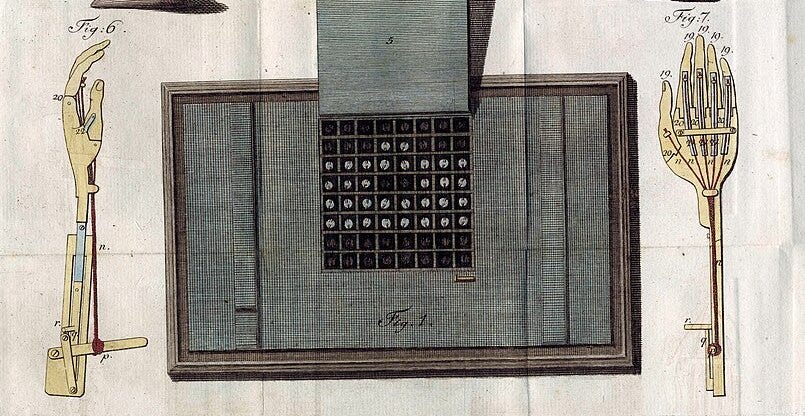

One of the creepiest services I’ve ever come across online is an Amazon service called Mechanical Turk. The service is named after a sideshow curiosity from the 1700s, a turbaned robot that could beat any human at chess. It was touted as a marvel of mechanical engineering. The trick was that there was a small person inside the Turk, controlling its movements.

Amazon’s Mechanical Turk lets you remotely hire people to do menial tasks for miniscule sums of money. Let’s say you have a task so repetitive and boring that your mind gets numb just thinking about it—e.g., changing every “5” to a “6” in an Excel spreadsheet. Through Mechanical Turk, you can hire someone else to do it at a tenth of a penny per change. A Pakistani worker changes a thousand 5’s to 6’s and you pay him a dollar. What looks like an automatic system from the outside is actually a guy frantically clicking and typing on a computer. Unlike their eighteen-century counterparts, Amazon doesn’t try to hide the fact that there are humans doing the work. In fact, the tagline for the service (now removed from the website) is “Artificial Artificial Intelligence.”

Every machine in human history needs to be operated by a human at some level. An ax helps you cut down a tree, but you need to swing it. A BMW gets you quickly from here to there, but a person has to design it, build it, maintain it, and drive it. No matter how automatic or magical a manmade object seems, it always draws on human power to function. The ones that seem the most magical are the ones that keep the human operator most hidden, like the Eternal Engine in Snowpiercer that’s actually powered by small children stuffed between the gears.

An AI tool is an elaborate machine that hides its human human operators so well that it seems to be thinking on its own. This is true on the input side, where thousands of workers in Kenya crawl through the opioid palaces of the internet and flag content that’s deemed “too toxic,” and the output side, where thousands of remote workers review the “choices” of self-driving cars.

It’s incredibly important for us to remember this. The worst part of AI tools is that they absolve people of their wicked deeds, or at least provide them with plausible deniability. Matthew Butterick aptly describes this as “human-behavior laundering”:

If AI companies are allowed to market AI systems that are essentially black boxes, they could become the ultimate ends-justify-the-means devices. Before too long, we will not delegate decisions to AI systems because they perform better. Rather, we will delegate decisions to AI systems because they can get away with everything that we can’t. You’ve heard of money laundering? This is human-behavior laundering. At last—plausible deniability for everything.

What AI really provides is an excuse. We’re not stealing your stuff. AI is. We’re not driving your car into an eighteen wheeler. AI is. We’re not whipping a crowd into a frenzy. It’s artificial intelligence. In other words, no individual person is responsible. It’s bureaucracy at its finest, the Orwellian passive voice writ large.

Dispatch from Broken Bow

I just returned from Jubilate Deo music camp in Monroe, LA, headed by the talented Mr. Richey, where I tended a book table for Little Word. Let me highlight the newsletters of three of my Monroe friends:

Z. K. Parker’s “The Try Works”

H. W. Taylor’s “The Enormous Room”

Jarrod Richey’s “Musically Speaking”

I should probably say that the views and opinions expressed in these newsletters are solely those of their authors, not mine. (That goes especially for you, Remy.)

Links

Here are a few extra articles about AI:

You may have seen articles about the copyrighted text and images that AI models spit out. I believed AI companies were guilty of massive copyright theft, until this article by Cory Doctorow calmed my outrage somewhat. He explains that Midjourney (an image generation site) keeps only about one byte of info from any given image it sources: “If we're talking about a typical low-resolution web image of say, 300kb, that would be one three-hundred-thousandth (0.0000033%) of the original image.”

Why AI will never topple the film industry: “To put it as plainly as possible, every single time that Shy Kids wanted to generate a shot — even a 3-second-long one — they would give Sora a text prompt, and wait for at least ten minutes to find out if it was right, regularly accepting footage that was subprime or inaccurate...”

Mary Harrington explores the scary idea that, thanks to artificial intelligence, using social media may become a form of social activism

Robin Sloan asks whether large language models are in hell: “The model’s entire world is an evenly-spaced stream of tokens — a relentless ticker tape. Out here in the real world, the tape often stops; a human operator considers their next request; but the language model doesn’t experience that pause. For the language model, time is language, and language is time. This, for me, is the most hellish and horrifying realization.”

Related to the above, James Bridle asked ChatGPT to design him a chair and, unsurprisingly, discovered that AI has no idea what an actual chair should be like

And lastly, Samuel Arbesman suggests we explore the “story world” of AI, since so much of the language input is in story form

Here are some other links of interest:

My friend Brian started a newsletter called Audio Deacon where he recommends and critiques various albums. If, like me, you’re pretty much clueless when it comes to contemporary music, now you have somewhere to start.

The US Surgeon General has advocated for a health warning on social media (via Jonathan Haidt)

This is my kind of humor (Faerie Queene humor)

Upcoming

Immanuel Reformed Church is sponsoring a lecture by Ken Myers on the Lutheran hymnal on July 15, at 9:00am, at Third Presbyterian Church. The lecture will kick off the Theopolis Ministry Conference, which is also very much worth your time. (Little Word will have a book table there, too.)

Immanuel is also sponsoring a concert by Joshua Davis, a pianist and budding composer on July 25, also at Third Presbyterian Church. Look out for more details.

I mentioned in a previous newsletter that I adapted The Scarlet Pimpernel into a stage play to be performed at my school this fall. The dates for the play are September 26th and 27th. I’ll send out more info when we get closer.

Up To

Reading: Malcolm Gladwell’s The Tipping Point

Watching: Sicario, ten minutes at a time. I’ve heard Roger Deakins interview so many of his friends about it that I finally decided to watch it.

Listening: Pimsleur’s Spanish 1

Eating: Peach croissant fritter at Caster and Chicory

About

I’m Christian Leithart, a writer and teacher living in Birmingham, Alabama. I’m not active on social media, but you can read my blog here. Use the button below to share this issue of Time’s Corner, if you so desire. Thanks much for reading.